Participatory Facilitation - an unfinished manifesto by Francis Laleman

image: In a workshop at The Common Ground, Bedok, Singapore 2023 (photograph by The Common Ground)

Facilitating the commons. Not doing. But doing by creating space for doing.

Somehow this works starts with Joseph Beuys, who taught us that:

► learning is the most artful way of being alive,

► to make people free is the aim of art, therefore art for me is the science of freedom,

► every human being is an artist, a freedom being, called to participate in transforming and reshaping the conditions, thinking and structures that shape andinform our lives,

► To be a teacher is my greatest work of art.

And also:

►Where would I have ended up if I had been intelligent?

And there is Gregory Bateson, and the idea of participant observation. We also love observatory participation. We don’t know. We choose to not know. At least not yet.

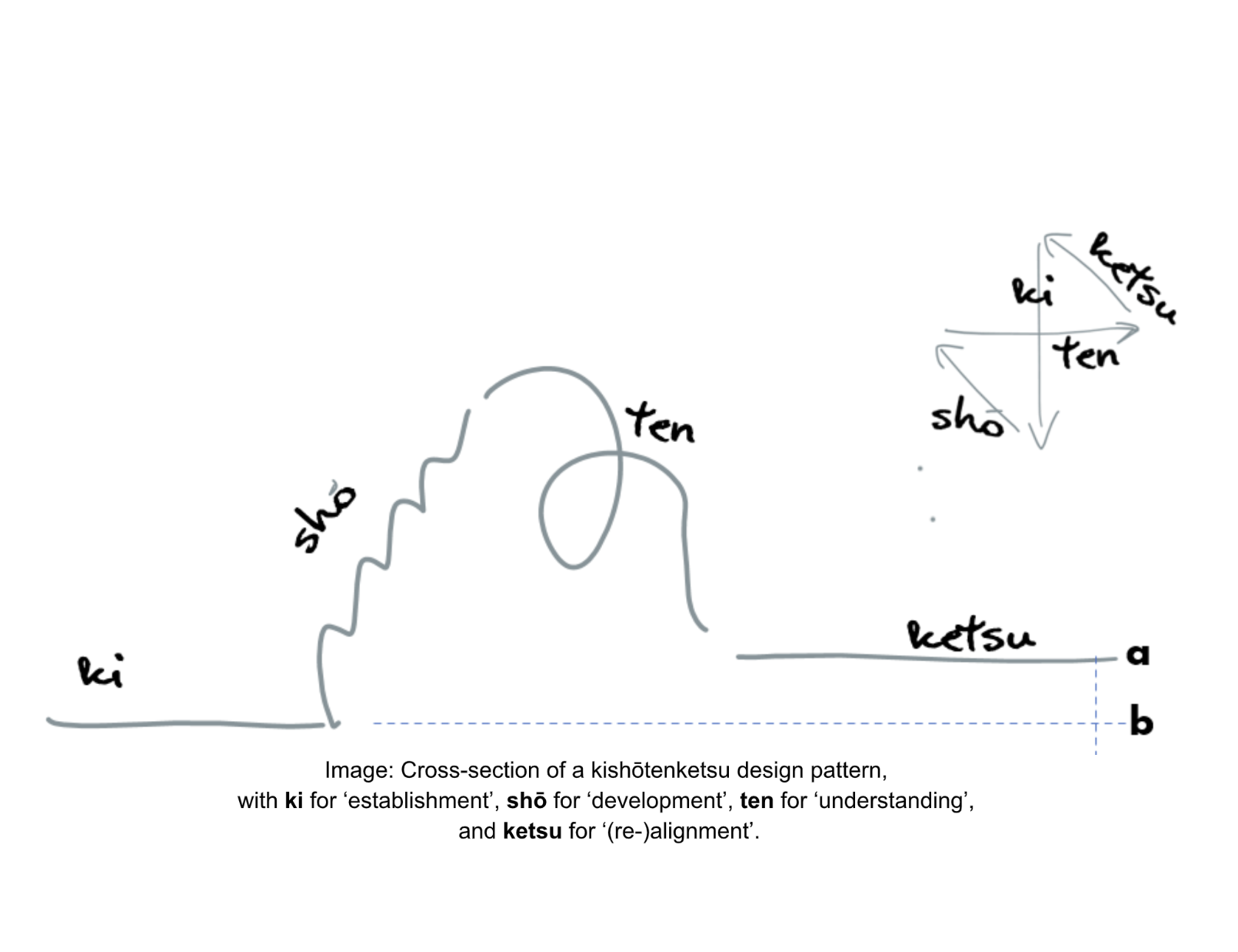

Of late we have been using the label kishōtenketsu (from the Japanese), qǐchéngzhuǎnhé (Mandarin), or giseungjeongyeol (Korean). We love these words because they are non-restrictive in their own particular way. They are no more than words for a pattern. A natural pattern. A narrative pattern.

Projected in common time and space, kishōtenketsu has four beats, representing the user experience of community members (and their facilitators, who are also community members, and vice versa) going through the experience of one iteration in the process, with an unlimited iterations stretched out in time. One beat is for context and space, one is for activities and experiences, one is for aha! and what we have discovered, and one is for getting ready to move on. And there it is: the basic texture of our tapestry, neatly folding back into itself like a Möbius Strip.

Texture, patterns, praxis

If the above is the basic texture and its weft and warp — then what is the embroidery, the filigran?

For the canvas to be truly participatory, the filigran, in the end, must be invisible.

Here are the ten most important and impactful bodymind features engrained in our facilitation praxis:

1 — We facilitate experiences

Facilitation is making individuals be at ease in groups and communities. Facile means easy but we choose at ease. Change continues to happen, with, among, by, and for one another. Community processes flow like a journey through life. No, rewind: they are a journey through life.

The collective is traveling a journey of learning and growth – and we must acknowledge the collective as a common owner of the experience. It’s not that they are traveling with us. It’s not that they are enjoying our hospitality. It’s not that they are supposed to follow what we think is our leadership.

The group is an entity of its own. The group affords for its own dynamics to emerge. In their process of transformation, the group is hosting us. The facilitator is invited to facilitate, to help the group get through the process unharmed, to help the group make the most of their lived experiences, to guide the group while it travels forward and transforms itself along the way.

To facilitate means to help a group be at ease with its lived experiences, as long as the invitation stands. Not longer. Nothing more. We must know our place.

Practical implications:

Stop “teaching,” activity-based learning, immersive learning, facilitate reflection, exformative learning, get away with hierarchies, zero PowerPoint, invisible facilitation, host-guest relationships, host leadership, tutorial relationships.

2 — Practice hodohodo

There is a lovely concept in Japanese design expressed in the word ほどほど (hodohodo), which vaguely means with moderation. We love the idea that a facilitator observes and feels and senses, but not “knows” what hodohodo means. Facilitators are participant observers. They postpone knowing.

In the best of cases the facilitator does (almost) nothing. Or visibly nothing. The best possible scenario is a matter of being there and taking care. And being there while practicing carefulness with hodohodo — with due measure.

Hodohodo can mean many things, like going just as far as is suitable in a particular situation. In other scenarios, hodohodo means to stop something before completing it — suggesting that sometimes things are best left unfinished and open-ended.

It is our commitment that from a facilitator’s perspective, hodohodo means designing and applying a bare minimum of constraints, and thus creating a space for the group within the boundaries of which it is safe, comfortable, and convenient to have crucial and critical but caring conversations.

Practical implications:

Work with a stable minumum of design, delegate facilitation proper, nurture affordance for curiosity, employ adaptive rhythm, iterative multi-modal learning, use abductive and transcontextual processes.

3 — Maximize exposure

While practicing hodohodo, the facilitator’s accountability remains unchanged. It is the facilitator’s accountability not to facilitate, but to help make it easy for the community to get immersed in lived experiences. Maximizing exposure has a quantitative and qualitative dimension. It means that the facilitator makes it easy for the participants to live as many experiences as possible, and live them as profoundly as the circumstances afford.

In brief, maximizing exposure means get in there and get in there deeply. Be there.

Be there — totally and completely. Breathe, interact. Live. Learn.

Maximizing exposure means creating conditions for the participants to remain utterly at ease and unaffected by FOMO. It’s all there. For the taking. There is nothing to miss. Learning and growing and evolving through lived experience is a fuzzy game. Whatever you miss out on, you gain the experience of missing.

Practical implications:

Offer quick iterations of activities and experiences (appealing to the whole array of senses), play the game of diversity, work on multiple levels and layers of understanding, keep an eye for meaningful engagement, be crisp, maintain cadence.

Always remember the relationship between shutter speed, your lens’s aperture, and the luminance of what happens in the moment: together these factors determine the amount of light that reaches the film of learning and transformation.

4 — Be a participant observer

In order for this to become even as much as an option, the facilitator must be an artful observer. We must watch — but more importantly, we must see. Which is so much more difficult that when taken at face value.

Seeing is achieved by going through the effort of moving. Bending. Stretching. Kneeling. Lying down. Looking up and sideways. Seeing differently.

Being a participant observer is identical to the practice of invisible vipassanā. The word vipassanā (from the Sanskrit vi-paśyanā, where the verbal root is paś-) literally means seeing differently. Vipassanā is going through a process of transformation, in order to see in different ways. Seeing from perspectives hitherto unknown.

There are many ways to practice vipassana-like participant observation. The art of seeing differently and helping others see differently by seeing differently ourselves. We are thinking of host leaderships and its multiple perspectives, viewpoints to behold a system from, as the participant observer that all of us inevitably must be, in systems so interlocked and intertwined in interbeing as system, with people in them, inescapably are.

Think of photography — and how the most informative photos are those taken from what we think is an absolutely neutral (though sometimes uncannily uncommon) observer’s point of view. Yet: the artist is present. The photographer is present. And the presence of the photographer does indeed have an impact on whatever it is that there is to be experienced in the room.

We might be observers, we are participants nevertheless. We inter-are. We are, but we are together. All of us are the system. We keep remembering: the invisible visitor is not just part of the system — when there, the invisible visitor is the system, just as much as all the other elements in it.

Practical implications:

Be present, yet invisible. Be invisible, yet present. Be a participant in the process without losing sight of the system, be everywhere (yet invisible), stay aware of the fact that you are the system too, data collected in the process are data collected in your inter-existential presence, create structures with different vantage. Profess mindful incidental photography.

5 — Practice mindful observation

Speaking of mindful. It is a well-known fact that humans only see what humans want to see, or what we are capable of seeing. The same goes for observation.

Since we are only capable of seeing what is already within the scope of the known, it must be that our observational skills are bound by the same limitation.

For this reason, mere observation is not quite enough. We need observation with intent.

With the word intent, we are thinking of several faculties all at once. Mindfulness is one: an absolute awareness of ourselves in our environment, where the ego is dissolved into inter-being so completely that it is no longer perceived as a separate identity. Focus is another: going deep into observing a phenomenon, without losing a sense of the object of one’s full attention being intricately interconnected with a myriad of elements that are currently not under observation.

Underlying conditions for mindful observation and focus are boundless curiosity, inquisitiveness, eagerness to know, and a profoundly liberating sense of wonder.

Mindfulness, focus, wonder, curiosity, inquisitiveness, and eagerness, are the bodymind features that drive the facilitator and the facilitated, all as one body, to live true experiences, and provide them with the ability to discern how the world’s cultures “inter-are.”

Be never content with the already known. Ventures to transcend the knowable.

Practical implications:

Work with questions much more than answers , asking real and clean questions is hard enough. Most questions originate in a space of known uncertainties or known unknowns. To go beyond, invite participants into seemingly random experiences. Do not let yourself get limited by targets and predicted outcomes of the process. Stay open-bodyminded. Anything might happen.

6 — Facilitate a practice of observation in others

If successful, mindful observation becomes a practice, and when practice becomes habit, we have gone through a life-changing transformational process.

This is the secret of kata, a Japanese word reserved for habits that get engrained so deeply into the “self” that they have become one with the very fabric of one’s being.

Now the facilitator stands in wonder for even the tiniest signs of interpersonal dynamics in their group, among the individuals, and between the human beings and their spacetime environment. The secret power of team is where human beings share their personal observations and insights with each other, co-creating common memories, collectivizing cultural artifacts and mentifacts.

A practice of observation isn’t so hard to get. It’s what a gardener does. A beginner gardener is one who wants to get rid of the weeds — which is easy because the only word we have is “weed” which means unwanted plants. Start by looking with more intent. See the beauty of the organism — not a despicable “weed” but a piece of unique beauty, volunteering on barren grounds, with exceptional resilience. Check for its name. If not, give it a name. Then, love it. Honor it. Why would you destroy that one volunteering plant and put an unwilling specimen in its place? One that needs to be kept in spite of its own nature and wishes? — Advanced gardeners don’t waste time and effort weeding away the weeds. They understand that the weeds are pioneers, heralding improvement of the soil, and creating the conditions for a better garden in the future.

From gardens and gardening, move to the interplay of shape and name, rūpa and nāma — and from this, go deeper into exploring the relationship between mindful observation and growing an intimacy not just with physical and mental phenomena in the environment, but with the words denoting them as well.

The essence of instilling in oneself and others the practice of mindful observation is in our continuous mindful interplay of rūpa and nāma (the phsyical and mental aspects of everything we do and discuss and study and learn). It is the art of walking one’s talk, but squared, and squared again.

Practical implications:

Tread softly. Go slowly. Walk the talk. Say what you do and do what you say. Call stuff and people by their names, while asserting hat nothing is just a name. Offer a variety of learning experiences and activities that afford for studying correlations between name and beyond-name.

7 — Play the semantics

Semantics is generally seen as the study of reference, signs, meaning, understanding, and truth.

Reference is where an object or a phenomenon is referred to by a substitute, using a certain sign or word or phrase.

Signs are placeholders for meaning.

Meaning is the relationship between signs and the things & ideas they intend, express, or signify.

Semantics is where we discover that how we understand an idea is only partly related to the idea itself. How we understand an idea is just as much related to who and what and how we are ourselves. This makes the idea of understanding a relative concept. Which is unsettling to say the least. When truth is dependent on the beholder, does truth still exist?

If truth is no longer universal, then what is the fate of concepts like love and hate or strife and vigour and moral value? And what when we explore and discuss change, transformation, workplace dignity, respect, courage, ownership, commitment?

Trying to read the world in all its complexity, and the intricate moral and ethical values of mankind, is like reading manga without any knowledge of its wordless vocabulary of lines and seemingly half-done scribbles. One might guess what it all means, but does it? And if it does or doesn’t, does it really matter? And if I think it doesn’t matter, what if there is a very specific grammar and syntax to all these signs, that eludes me?

Am I going to miss out on the great game, by sheer ignorance of its rules?

Practical implications:

Never take for granted that participants are on your (or each other’s) page. Keep checking for different ways to come to “truths.” Make participants express understanding in different ways. Use objects, drawing, painting, chalk, play. Use metaphors. Collectivize expressions and “understandings” with pay-it-forward choreographies. Keep wandering. Keep wondering. Stay away from the big certainties: they do not exist.

8 — Withhold judgement

With practice of observation and practice of semantics, as discussed in points 6 and 7, a sense of withholding judgement is bound to come by itself. With our minds full of wonder and unanswered questions, judgement comes across as the kind of spectacle one engages in only when one is ready to make a fool of oneself. Here is where we find that practices #1-to-7 have overturned the very fabric of how we have moved onward, to a new, different kind of plane, invisibility, where judgmentalism is left behind — a mere barrier now, rather than a lever to the assertion of self.

Practical implications:

Keep asking questions. Keep making everyone doubt everything. Please guessing games. Juxtapose messy conclusions with Clean Language. Help the group (yourself included) learn, not know.

Learning is a meta-skill. Knowledge is for beginners.

9 — Postpone opinions

What is left is a community, a group of human beings on a trail of discovery, where even opinions are postponed. What, at this point, is the alphabet of the invisible space we create? The answer comes with primitive reflexes, righting reactions, equilibrium responses, readiness for relating, to earth and heaven, gathering, spatial reaching, supporting, the protective extension, homologous movement, and much more in a long list of mindful practices within easy reach of anyone willing to let go of self, abandon the certainties of auto-reflective views, and move on.

Practical implications:

Keep accentuating the difference between opinions and possibilities, between lived experiences and their petrification in opinionated stances.

10- practise kindfulness

In the end, there’s only kindfulness. We perpetuate that word - a portmanteau for kindness (karaṇīyamettā) and mindfulness (vipassanā) — a meaningful mixture, for it is through the special way of seeing (this is the literal translation of the word vipassanā) that kindness (mettā, from the Sanskrit maitrī, “such as occurs among friends”) takes root.

Facilitation is an invisible participatory activity, open to be perceived only in the kindfulness filling its space. After all, we are making it easy for one another to participate and learn and evolve and adapt. As soon as the participatory nature of the process is clear, mutual kindfulness is on its way.

Invisible facilitation is an act of kindfulness — a gently facilitated space, but just enough, with maximum exposure to the as yet unknown and un-understood, with full awareness of one’s own immersive, invisible participation even if one attempts to merely observe. But observe we must, with intent and curiosity and eagerness to experience, and carrying this eagerness in basketfuls to be shared with others — when in the end we meet, transformed, and weaving conversations into fabrics of belonging, with the warp and weft of semantics, unpeeling our former opinions layer by layer, and leaving nothing but kindful appreciation.