"I want to explore how the void can function as a place of connection" - Dimitri Machas

During their architecture studies, Dimitri Machas developed a particular interest in public space and commons. Thanks to their professor Stavros Stavrides, they found a perfect partner in Timelab. The project they developed during their five months residency in Ghent is now awarded with one out of three Bouwmeester Labels 2025. – Elien Haentjens

Why did you choose to focus on public space as an architect?

“In Athens, we don’t really have public spaces. We don’t have parks in the middle of the city. You can’t just take a ten-minute break of work, because everything is closed now. Everything is turned into commercial usage that stimulates the citizen-consumer way of living. Even ancient squares got the allure of shopping malls. This violates us, because it makes us less connected. So, I think we need to revitalize public space and make an effort to bring people together without too much distraction.”

Which projects were you working on in Athens?

“For our master thesis, we set up a project to revitalize the courtyards of Athens. We turned these into viable spaces for people to live, while they were normally left abandoned. Besides we also made statements with our school towards the government. As Greece is the entrance to Europe, we also host a lot of homeless refugees. At the same time, lots of buildings are empty. So, if you combine these two, the solution is right there. But we keep finding ways to restrain ourselves from revitalizing these empty spaces.”

How did you start your project at Timelab?

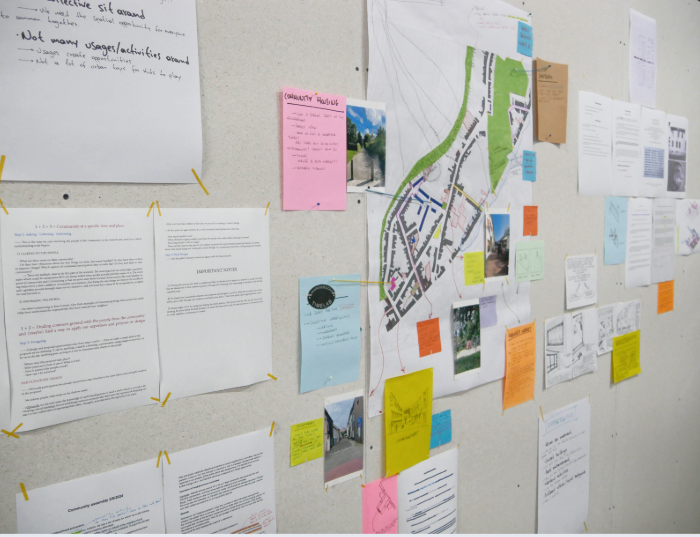

“For me projects and interventions always need to have a place. Places are attached to people, and all people have different cultural backgrounds. So that’s why I wanted to understand the neighborhood. I was walking around and talking to people, and I was also welcomed to their community assembly.”

“During that process, the fences between the backyards gradually took my attention. In the city center of Athens, we don’t have singular family houses, private gardens or fences. Courtyards of apartment blocks are open, creating one big common space in the middle. So, I started wondering why one would need a fence, if you know your neighbors. This question became very intriguing.”

Did you ask the opinion of some people?

“Mostly, they said it’s a sense of safety and a way of demarcating their territories, ensuring their privacy. But personally, I believe that you can still have your privacy, even without a fence. You just must set your boundaries towards your neighbors and learn how to deal with other people. Moreover, safety comes through knowing each other. Living without fear gives a sense of freedom. You also need to trust each other, to be able to make actions together. So, my project is among other things also about the sense of safety that the fence represents, and if it’s an illusion or not.”

“In terms of public or shared space, taking away the fences would transform the small gardens into a huge backyard, which could house for example a community sports courtl. So, it’s a way of opening up to new possibilities. It’s important to have a public space that is more alive than your own home. Your house is like a vestibule to relax, sleep or chill down. We must see the public space as a way of becoming political. It’s

about confronting each other in a commonly way.”

“Probably a lot of the people also just didn’t really think about the fence. They just put it because everyone else does. So, I would like to spend some more time in understanding how even fences impact our lives because I think they do. To understand ourselves we should question ourselves more and communicate with each other. The continuation of my project in the context of the Bouwmeester Label is to stimulate discussion.”

How would you like to encourage this?

“I want to invite neighbors to make a small hole in their fence. I suppose they will become curious and would like to start looking inside and working together on new possibilities. But from that point on, it’s their decision how to deal with it. Architects should rather propose ideas, but the people should realize them as they live in the spaces. Architectural despotism should be abolished, at least in the sense of dictating human behavior in space. I don’t think it’s about answers. I’m just curious in trying things out together and to see how we can improve our lives and occupy space in a better way.”

Which values do you share with Timelab?

“Timelab is also strongly involved in commoning. As democracy is failing, these are very frightening times. Although power will probably not go away, I believe commoning is about a way to find possibilities to redistribute this power and to find networks to not make this power get accumulated. So, everyone can be equal in that form of power. We only need to accept each other’s differences. I think Timelab does accept individualities. They try to give people voices, acknowledging people for who they really are, not viewing them as numbers as societal constructs do.”

“Thanks to its open, inviting space, people can come inside and make a difference coming here. Everyone gets the same say. While I was working on my board, random people from the neighborhood were curious and came in. Which was super nice, because my projects are about the involvement of people.”

Is your philosophical view influenced by your culture, with Greece being the home of democracy?

“There are two kinds of democracies. In the ancient Greece kind of sense, it was a more immediate form of democracy. Every three months, the assembly was changed, so it was near to impossible to accumulate power. Now you get elected for four years, which gives politicians too much authority and which slows down too many decisions. So, I don’t think democracy in the context of the government is still working. Moreover, it’s mostly economy that runs politics. As I’ve experienced how the government screwed us over after the big crack in 2008, I’m always a bit distrustful against governments. We always need to continue critiquing things to understand how things are happening.”

“Besides, there’s a more immediate, activism kind of democracy, in the sense of standing up and raising your voice against injustice. This doesn’t mean that all street protests can change something. But even if it fails, you get the sense that something is happening, which gives you hope. Being connected and exercising solidarity is important. It also changes your mind. We need each other, so we need to become less individual again, leaving our social media bubble. Connecting with each other and caring for each other is our responsibility. It’s the true essence of being a political being. So, in this sense I’m very optimistic: if we unite communities and start to obtain individual appellation, we can make a change in these precarious times.”

Which role could architecture play in this?

“I’m a bit fearful of the pedagogy route architecture is taking, as I would like to see that kids get motivated to be more curious. It’s important to keep asking questions and communicate with other people. When I was eighteen, I was full of questions. I got the sense from teachers that architecture is an answer to things. But I was always wondering about the opinion of people who would work or live in the building. Nowadays students conceptualize digitally, following the starchitecture contemporary path.”

How is this view related to your fences project?

“It’s important to keep questioning our world and try things out, like the holes in the fences. What I try to research, is how space appropriation and common usage of space activates the political essence of being. As historian Hannah Arendt once said politics are not in the essence of a human being. It happens when we confront each other. This used to happen in public space, but as this space became too commercial, we don’t do it anymore. While you exist in your house, you coexist in public space.”

“In between the public and private space, we have the intermediate space, like the backyards and the fences, which could function as a space to start being political just with one neighbor. While the fence is the boundary for this confrontation, we should explore this boundary as a potential void that can connect people. Commoning should be an organic process, in the sense that it starts as a one-on-one conversation. The void can be explored as a thing that mobilizes commoning.”

“On the scale of a country, I just have a ballot and a piece of paper, once every four years. But on the scale of a community, I do have a voice. We should try to shift society to community, and alienation to connection. You just must remember to not keep these communities enclosed, so it can keep spreading.”

Is a city as Ghent or Brussels the right environment to do this?

“It would be much easier in the Greek countryside probably; in my village no one had their doors closed and people live more outside. As the neighborhood around Timelab is something in between, it might be the perfect place to try some of these commoning initiatives. Although I would also like to explore the possibilities in Brussels, as it resembles Athens. In a bigger city we can start on a small scale, such as an apartment block.”

“We also had the idea to do something with food. In Greece, we’re always eating together, as food connects people. So, maybe we will also host a dinner at Timelab.

We’re not just these robots that only work all day. We should also explore our feelings and sentiments. Sometimes it should be just about having fun, about trying new things we don’t know anything about. We should allow playfulness and not be afraid to make mistakes, just as kids. Although I’m also worried how today’s kids will evolve, as they’re not interested in playgrounds in public spaces anymore. This means that they don’t start to get interested towards each other, or caring about each other.”

The project is also about designing the void. What does that mean?

“I’m trying to explore design as a way to subtract things and take them away. We’ve already built enough buildings, walls or fences. I think it would be more interesting to see how we can take things away and open the space, so we can breathe more. I want to try to design the void and emptiness and explore how the void can function as a place of connection, because a wall is just a barrier. The holes or pores which allow you to see through are a kind of void and are the starting point to connect with people.”