Wait a minute. Where is the artist?

The central question of the artistic research of Timelab is the position of the artist as an individual, as a peer group and the position of the arts as a field.

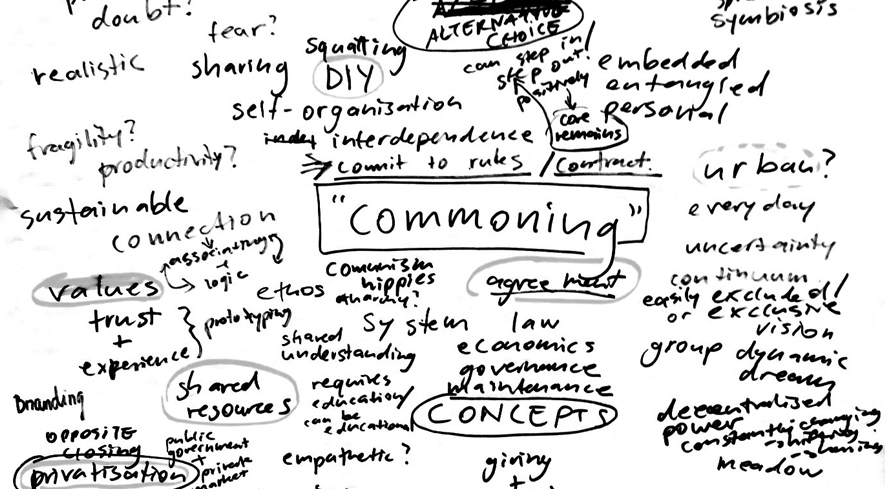

“We question current systemic appearances of the arts world and many other domains. We look for inspiration in the commons, nature, hackers and culture.”

This overall research takes place in a context where empiric projects build a tangible lab environment. Our projects balance on the verge of the cross domain and intersectional artistic experience and functional outcomes and create an artistic experience over time.

Timelab Method: a continuum

Artistic research

Let’s dive deeper into the meaning of artistic research to understand what makes research and development artistic and what is R&D without the arts? Or better, when is research artistic and when is art research?

Research is "any creative systematic activity undertaken in order to increase the stock of knowledge, including knowledge of man, culture and society, and the use of this knowledge to devise new applications." (OECD Glossary of Statistical Terms, 2008).

This definition gives no exclusivity to the scientist to execute research and shows the importance of creativity and a systematic approach as key for research. The need to increase knowledge and use knowledge in an applied manner does sound familiar to many of the artists around. Perhaps the dominance of a scientific worldview makes it hard to accept that the arts practice belongs to research or that it’s the lack of resources that creates the protective reflex of the scientific world to exclude arts from research except if it is an artist that is ‘researching’ and is therefore entering the world of science. Although the diversity in scientific research from social to exact sciences and behavioral studies is as big as the diversity in artistic research.

In many cases, one could say arts is using research for creating arts, which results in arts being research.

Despite the need for singularization, arts and science seem to be two dimensions of a continuum, of a common cultural space. Which brings us to the question: what defines the level of artisticity in research or the level of research in artistic practice? It is clear: research is not only artistic because carried out by an artist, as also research is not only scientific when carried out by a scientist. What makes research artistic is the mode of artistic experience. Julian Klein, composer and director of the Institute for artistic research, Berlin describes the artistic experience as part of his Artistic Theory of Relativity :

“The artistic way of seeing the world encompasses an awareness that we find ourselves in a reality outside of that which we regard as the content of our perception. A sort of brink exists for us, an edge separating us from ‘the other reality,’ whether that be ‘the assumed reality’ or ‘the invented reality.’ This does not mean that a ‘real’ reality is less constructed than an ‘invented’ one, nor does it mean that we are ‘more’ in the ‘real’ reality than we are in the ‘invented’ one (on the contrary!); it solely means that we know ourselves to stand with one of our feet in one reality while operating within another reality. This distinguishes the artistic mode from other modes of framing, like the framework of a game. In a non-aesthetic game, we typically find ourselves completely within the framework of the game – as a soccer player, as a chess player or as a ballroom dancer. If a portion of our awareness, however, is still watching the framework from the outside, it is precisely this that forms the artistic part of our perspective; the point at which we see ourselves as being within a second framework is always the point at which we observe ourselves from the outside and thus from an artistic perspective. In an event parallel to the aesthetic sensing, we become aware of how it feels to enter the framework. The artistic way of looking at things is a perceptual mode that accompanies us constantly and everywhere, just as aesthetic sensing does. Because of this, art (as a means of observing reality) cannot be separated from perception, since it is always present at the very least as a possibility – even outside of art-works and art-places. This is the main reason to speak of artistic experience instead of art in the sense of works or artifacts.”

Artistic experience is an active, constructive and aesthetic process. In that sense, artistic research must also be a mode of a process. So, when is research art? The time perspective is key here. In the course of a research, artistic experience can occur at different times, be of different durations and different importance. It occurs and we can only define the phases afterwards. Although Lesage distinguishes object, method and product categories.

Research can be artistic in the methods (such as search, archive, collection, interpretation and explanation, modeling, experimentation, intervention, petition,…), but also in the motivation, inspiration, in reflection, discussion, in the formulation of research questions, in conception and composition, in the implementation, in the publication, in the evaluation and in the manner of discourse.

So, how then do we reflect on the level of arts in the research? Even though the reflection can take many forms, it does not appear from the outside. The artistic experience is reflection.

We can think of many complex issues that are, as a research question, common to scientific and artistic interest. The artistic experience as a mode of reflection can build knowledge that can not be developed otherwise. This knowledge is inseparable from the art itself and has to be gained through an emotional and sensory experience. The artistic experience is embodied knowledge.

Practical research

Another juxtaposition in Timelab is the empirical versus theoretical research. Theoretical or academic research is based on a hypothesis or theory, while we base practical research on practice or action and on iterations of sometimes minor gestures. Although the distinction is often not that clear, both types of research use a different methodology. The effect of the endless and open ended loop of learnings and buildings is the creation of streams that connect past with present and future.

The empirical approach will often lead to a broad range of learnings and understandings that are accessible through projects physically translated in the space. By alienation of spatial experience, by creating an atmosphere of belonging, by creating obstacles, we create ‘becomings’. Our space is about what we want the world to become.

The organisation becomes the framework as a research environment for well-defined research questions that brings critical topics to the surface. The living lab environment creates the opportunity to define artistic research in a lab environment in order to develop strong research findings on a systemic level. This framework includes embedded projects within different fields, such as industrial production, urbanisation, education, sustainability, governance and participation strategies, structured in what we call the streams.

The artistic residency (AiR) is not a service

We want to introduce you shortly into the format of the AiR as a central part of the artistic program. Over the years, this format took many forms. With a short historic overview, we want to position ourselves in the world of artists’ residencies. For a list of artists in residence in Timelab, we refer to the annex.

Although best known from the romantic 19 and 20 centuries where patronage offered a place to stay and work to various artists from abroad, the dominant model of arts residencies emerged in the 1960s offering artists to withdraw from daily life into an escape or, the opposite, a period of work in a local community, often with a need for social or political change. Artists-run-residencies developed an alternative exhibition circuit and made the residency work more visible. In the late 80 and 90s, the globalisation and high mobility of people influenced the arts residencies. An international and intercultural encounter brought the hosting organisation to the foreground as an independent connector and catalyst of the global art world and the local contemporary art scene. The residential arts center started forming an international fabric of knowledge and experience in the arts. After 2000, this network further intensified and consolidated. With this evolution, also the need to explore the meaning and value of AiR grew.

Digitalisation and social media, cheaper and easier traveling, profoundly diversified and enlarged the field of residency places all over the world. They organised as a field, advocate for their being and with this the competition took off. For many artists, residencies became an important part of their career. Quality standards and selection procedures became an important part of the work of the hosting organization. In this evolution, we cannot deny a rising market logic getting a grip on artistic practice and autonomy of the arts. The AIR risks to bite itself in the tail. Born to disconnect from daily pressure and to have a full autonomy of the creation in order to crack open unseen layers of the mundane, the free form of the AIR becomes a service. As a reaction, hard to grasp models of residencies came into existence. The fluidity led to the rise of more thematic residencies. The focus on the model of working shifts to the ‘what’ we are focussing on. The topics, more and more often becoming topics of sustainability and complex societal issues, also are a hook to work interdisciplinary with experts on the field from different perspectives. Both organisations and artists are rethinking their role in society and the cultural field. The artistic practice develops towards artistic research. Residencies offer other spaces and models for the development of knowledge, not only in the arts, but in society as well. The role of the host to capture and develop a knowledge network, known from the sixties residencies, breaks through the boundaries of the arts scene and delivers more often a necessary contribution to all kinds of research and development. We see businesses inviting artists to develop or redesign products and services or throw another perspective on the non-arts environment. An approach embraced by some, banned by others.

Artists in Timelab over the years:

Nicolaus Gansterer - Juliana Borinski - Geert-Jan Hobijn - Duncan Speakman - Kaffe Matthews - Z. Blace - Vasilis Niaros - Stefan Klein - Thomas Lommée - Andrew Patterson - Einat Tuchman - Filip Berte - Cliona Harney - Pia Gruter - Eugenia Morpurgo - Robbert & Frank - Helen Milne - Gosie Vervloessem - Ingrid Vrancken - Helena De Smet - Jesse Howard - Kai Lossgott - Lena Skrabs - Marc Buchy - Paloma Sanchez Palencia - Rachel Himmelfarb - Remy Marlhioud - Rasa Alksnyte - Tiny Coopman - Wendy Van Weynsberghe – Lies van Assche - Wouter Huis - Agoston Nagy - Gert Aertsen - Gina Haraszti - Hendrik Leper - Jean Noel Montagne - Jodi Rose - Kasper Konig - Maja Gehrig - Pierre Laurent Cassiere - Pieter Coussement - Pieter Heremans - Tim Knapen - Tom Verbruggen - Andreas Zingerle - Angelo Vermeulen - Eisa Jocson - Frederik De Wilde - Geraldine Juarez - Juan Duque - Maria Lucia Cruz Correia - Marie-Laure Delaby - Naomi Kerkhove - Niklas Roy - Paolo Cirio - Wouter Decorte - Yannick Franck - Els Viaene - Javier Busteria - Jon Cohrs - Karel Verhoeven - Kathy Hinde - Laia Sadurni - Myriek Milicevic - Roberta Gigante - Silas Fong - Stephen Verstraete - Vahida Ramujkic - Karl van Welden – Laurence Payot – Dusica Drazic – Britt Hatzius – Marthe Van Dessel – Korinna Lindinger – Thomas Laureyssens – Vlad Nanca – Tom Kok – Hans Beckers – Sara Vrugt - Alice Vandeleur-Boorer - Maria McKinney - Saara Hannula - Delany Boutkan - Steven Humblet - Chris Swart - Alexandra Laudo - Sun Lee - Louis-Clément Da Costa - Patty Jansen - Gabey Tjon - Maité De Bievre - Anthony Teston